Saturday, December 08, 2007

Tuesday, December 04, 2007

As Winter Hits Rural Northeast Kazakhstan, the Lights Go Out

The moment we had walked out of the school building the lights had gone out and a wave of darkness had splashed over rows and rows of neatly placed identical one story houses. The village was usually dark enough at this time that to walk down its ice streaked paths meant having to slowly place each foot cautiously in front of the other, a faint light the only means to differentiate between earth and ice.

The moment we had walked out of the school building the lights had gone out and a wave of darkness had splashed over rows and rows of neatly placed identical one story houses. The village was usually dark enough at this time that to walk down its ice streaked paths meant having to slowly place each foot cautiously in front of the other, a faint light the only means to differentiate between earth and ice.This faint light came from the last remaining street lamp, a flickering bulb that sat at the top of a not too sturdy looking steel pole attached to the side of Ivan Vsilivich's store

. The only reason it worked was because Ivan Vsilivich fitted the monthly electricity bill, a marketing strategy that had backfired horribly. Instead of real customers, the sole street lamp attracted a swarm of hooligans who loitered in front of his store like gnats around a frat house porch light. Occasionally they bought a 2 dollar bottle of vodka or a pack of 50 cent cigarettes but it took only one glance across the counter at Ivan Vsilivich's all to hardened face to see that the business wasn't worth their presence.

. The only reason it worked was because Ivan Vsilivich fitted the monthly electricity bill, a marketing strategy that had backfired horribly. Instead of real customers, the sole street lamp attracted a swarm of hooligans who loitered in front of his store like gnats around a frat house porch light. Occasionally they bought a 2 dollar bottle of vodka or a pack of 50 cent cigarettes but it took only one glance across the counter at Ivan Vsilivich's all to hardened face to see that the business wasn't worth their presence.The street lamp flickered its last few breaths of life before it too was consumed by darkness. The hooligans began to slowly disperse now in search of a more suitable place to congregate. A steady snowfall had begun and was beginning to blanket the ground, creating a soft protective layer over the ice.

Instantly the shape of the village changed. Time within its modest borders had lost its rhythm and the shadows of assorted automobiles and satellite dishes now peered curiously against the an unfamiliar darkness.

Inside the rows and rows of neatly placed identical one story houses, people lit lanterns and carried them beside their dinner table. The food that they ate, the cabbage, boiled meat, carrots, salt and potatoes had been there for as long as anyone could remember, as were those creaky wooden chairs and light tin utensils.

As I walked down towards the store, I thought about walking in and seeing Ivan Vsilivich sitting there, his face smooth his demeanor undisturbed. I wanted to see him with his comrades, drinking to a future where he and his family would be protected from the evil that permeates life so often and so deeply. He would raise his arm, bellow a toast and confidently empty his glass. I wanted to see him before all the other streetlights turned on and then so abruptly turned off, before he became so frustrated, so confused.

Just as a deep uncertainty comes from the darkness, so does a hope. What's that they say, its always darkest before the dawn?

The light turned back on, the hooligans regrouped and the rhythm of the present reclaimed its rightful place.

Wednesday, September 12, 2007

Autumn begins in Vinnoye

Fall chickens in the backyard chicken coop

Fall chickens in the backyard chicken coop Baby ducklings with their mother take twenty minute tours across the garden ten times a day

Baby ducklings with their mother take twenty minute tours across the garden ten times a day By November these guys will be served with a side of buckwheat

By November these guys will be served with a side of buckwheat "Baba" Ira prepares tomato juice by grinding fresh tomatoes, onion and horseradish; the juice can be stored all winter.

"Baba" Ira prepares tomato juice by grinding fresh tomatoes, onion and horseradish; the juice can be stored all winter.

Monday, September 03, 2007

First Bell for the Second Time

First Form Students Start School

First Form Students Start SchoolTuesday, August 21, 2007

Not a typical summer hat

The transfer is agreed upon.

A Summer Stroll

The first question is obvous. Where is this newcomer going at such a pace? There are only a few places someone could be headed on foot in the village of Vinnoye. The skola, the hospital, horsefarm, the local shop or maybe somewhere over kruglia hill, to uncharted lands. It's a Sunday the one day where people put down their hoes and lay their frames to rest, so that cancels out the skola and horsefarm. He could be headed to the hospital, but there's a small remont there, an installation of new chinese made windows: a step down in quality from the old soviet one's which we stolen sometime between '92 and '94, but what can be done as the good ol' days are long past by now. He could be headed to Ivan Vsilovich's shop, but everyone knows that pensions are already two weeks late and that means Ivan Vsilovich shelves will be more bare than the old men who every June plant potatoes in nothing but black speedos.

One would be lucky to find a bottle of Slavyanka during a dry spell like that. Kruglia hill it must be, but who walks towards Kruglia hill on a Vaskresenya afternoon with such determination in his glazis? There is no rifle on his arm so he can't be going there to hunt rabbit or ptitisis. He goes alone and carries no blue tarp or large rice bag neccesary for an afternoon picnic. There is really only one possibility left, that his brats already headed out for a picnic and he is meeting them, extremelt late and in a great hurry. Yes, this could make sense, but why is he not carrying any podarkis with him? At the very least some smoked fish and piva are neccesary if a friend is meeting his tovarish fo a nice Sunday afternoon picnic. This poses a serious problem and is cause for real concern. After all, if chapter two of this year's book is different from chapter two of last year's book one could make the argument that the third chapter would be different as well, making the whole year's book different and eventually completely changing the story dramatically. In the entire history of the village there has been very little real change, of course there was that one time when the Ivanovich couple took15 potatoes from a neighbours yard without asking but that situation was resolved with the potatoes being paid for.

The concern now can be seen on the faces of two babooshkas sitting on a nearby bench, the constant pace of their croquet needles slowed to a halt. The light sound of their gossiping is all that is heard as a young fourth form girl suddently sprints in the middle of the path, picks a fresh sunflower from the earth and intercepting the fast paced figure, presents it to him. The six foot figure accepts the svetok and with a smile brewing on his face, peers deeply into the midday sky and continues down the road at a much more respectable pace. The babooshkas breathe a sigh of relief and the rotation of their needles starts up again. The chapter, the book, the story, the history will be preserved. Where he was going, nobody ever knew.

Saturday, May 05, 2007

A simple funeral

.jpg)

Walking down the long, funneling dirt road that marks the border between Vinnoye and open space, something very peticular and equally peculiar catches my eye. It is a color usually reserved for not so simple places, yet fused into a shape ubiquitious with those who have been humbled by the land. The color stands out like the blood of a calf torn apart by wolves that I came across in the snow of the previous winter. Much like the calf and much like this village, it simultaneously intrigues and horrifies me. I quicken my pace, weaving around some young children playing with the now yellowed bones leftover from a previous meal, their faces covered with a dark grey soot. "Zdrastvootie Mr. Robinson!". A step up from the "Kak Sam"'s of Avat I think.

I look up and at once notice that a large crowd has gathered in front of a house, which from the distance I'm at seems to be parellel to mine. They are standing in a semicircle, wrapped around the back of a blue rusted truck usually dedicated to transporting hay and grain. Their faces are somber, long and gaunt. Well, I think, their faces are always somber, long and gaunt. I turn my eyes to a recognizable face smoking "Medeo" cigarettes with fingers already caked with dirt from a half days work. He always smokes Medeo cigarettes and the dirt on his fingernails seems as permanent as the row of smokestacks that line the horizon. I hear a faint distinguishable sound and as I turn to look at what is within the semicircle of villagers I notice an older woman crying as two men prop up a wooden coffin into the back of the truck. A man turns on the engine and the truck slowly begins moving at an equal pace with the now growing crowd. A sense of unity pervades the chalky air as the crowd follows the grieving woman who follows the truck which follows the funneling dirt road, around a bend and towards the westernmost of three semicircular hills protruding from the earth.

Lying on the far side of "kruglia" or the aptly named "round" hill is a makeshift graveyard, where in its 150 year history the men and woman of Vinnoye have been returned to the same earth they spent their lives toiling. A hastily constructed stone fence protects the graveyard from wandering cattle. I join the end of the crowd and ask the man with the recognizable face "shto sloochilas", what happened? "Eta stari dyadooshka, on oomel. Oh bil voseemdesiate chitiri goad." It's an old grandfather who died. He was 84 years old. "Tui znal? On bil tvoi sosiedi". Did you know? He was your nieghbour. The truck continues up towards kruglia, the outline of a scarlet cross permeating the white birch wood of the propped coffin. "On bil harasho parin" says another familiar face who overheard my previous question. He was a good man.

Friday, April 27, 2007

Real, Live, Stock.

I wander across the schoolyard, through a gate and in between two large stockpiles of hay. I open the gate to the other English teachers home, her house a one story building equally long as it is wide stands on the left and a small barn stands on the right. She has invited me to see her new piglets, because she knows that living my whole life in New York City means this will be a new experience for me. Her excitement runs through her body and out through her eyes and the corners of her mouth as she opens the barn door. The litter of eleven piglets squealing behind the door means an improved life at least for the next 12 months, granted they all survive. Once they reach full size, she can sell each one for around 200 dollars. That’s up to 2200 dollars or enough money to pay off loans, maybe buy a few heads of cattle and even have money left over to purchase a 25 year old Soviet made Lada, still the best made cars in the world.

So I walk into the barn, the piglets shiver and huddle in the corner of a pit of wet mud. My friend picks up the unlucky one unable to crawl his way into the middle of the pile of pink fur. She baby talks him and holds him in her arms, petting their little heads with her fingers as if they’re her own children. Much like her children, these piglets have brought her hope and happiness.

.jpg)

The sun lingers on the horizon and the last few sheep and goats scamper back into their barns. The last few sounds of sticks whipping against hide and the trotting of horses echo in the distance, then a few words in Russian and the slamming of a wooden gate. It is spring, and the lives of the people of Vinnoye are starting to coincide with the lives of pigs, cows, sheep, goats and horses. It’s a codependence that has existed for thousands of years, that somewhere deep in the history of our families was once understood fully. In the year 2007 in Vinnoye, Kazakhstan these animals serve the same role that they did 3,000 years ago. They are more than hamburgers in wrappers. They are the promise of a better tomorrow. I think there’s something beautiful about that.

Sunday, February 25, 2007

Friday, February 23, 2007

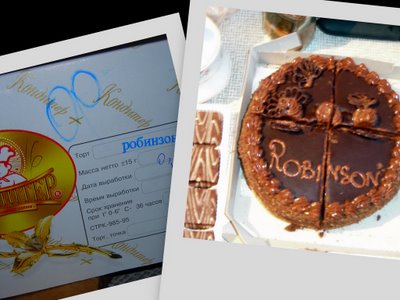

The Robinson Cake

Friday, January 26, 2007

Watchdogs of Vinnoye

REX

REXThe role of the dog in Vinnoye and in all of Kazakhstan may still be considered that of a man's best friend, but for primarily different reasons. These dogs arent spoiled with brand named dog food, taken on walks or even given a pat on the head every now and then as they might be in America. They are watch dogs and it is the hate and anger they exhalt, not an unyeilding love that gives them their value. There is an unwritten understanding between dog and owner. It is unwritten because the dogs cannot write but even if they could they would not know how to express themselves. Any emotion has been removed from their minds and souls at a young age. They are trained to hate, one could say they are professional haters. What remains is their end of the bargain, an unrelenting blood red hellbent almost psychotic rage against every moving object, living or non living. They have this uncanny ability to bark nonstop literally for hours at a time. The owner in turn gives the dog enough stale bread and chicken, duck or fish bones to survive, and a small wooden house to lie in when the weather dips below freezing. The dog that reminds everyone that passes by my small house that he has acquired the gift of unemotional, hateful gab, is named Rex. Rex is two years old and all he has ever known is the five square feet of land that his chain allows him to survey everyday. He knows that the only person in this world who he respects is his human mother, Irina Safonivna and maybe also that new tall American, but thats really still up in the air right now. He really respects Irina Safonivna because she gave him a place to stay forever. She was the only one who was there for him. Everyone else is an intruder and a threat who must be barked to death at any cost. Nothing can get in the way of Rex making sure that his hate is heard, loud and clear. If his bark could be translated into English, he would just be saying, "I hate you, I hate you, I hate you" over and over again. Maybe an "I don't like you" or "God, you are pissing me off right now" thrown in there. It's ashame really, because deep down I think Rex is a good guy. If he just was taught that there is such a thing called love in this world I think he would be more than capable of finding happiness within himself. Maybe if Irina Safinovna didnt hit him in the face with a 2 by 4 everytime he barked at an intruder that was actually a friend of hers he wouldn't be so confused. He is only two years old and probably could be salvaged at this point in his young life. But then again, what does he need to be salvaged from? In this chaotic, hateful, dog eat dog world, this is his role, and he's damn good at it.

My next door neighbor's dog is half wolf and equally angry at the world.

My next door neighbor's dog is half wolf and equally angry at the world.

Saturday, January 06, 2007

Life on Mars

The road from Ust Kamenogorsk to Jenghis Tobey (the train station to Almaty) looks more like the surface of Mars. This rocky mountainous looking hill used to be used as a monastery during the 15th century supposedly. When we were driving by the sun and the moon both shone brightly in the sky. It really felt like another planet, the planet of Kazakhstan.

SP_A02155.jpg)